The history of the bandana

The Bandana: A Historical and Cultural Exploration

The bandana, a simple yet highly symbolic accessory, has a rich history that stretches across continents and centuries. From its origins in ancient Persia and South Asia to its place in contemporary fashion and protest movements, the bandana has evolved into much more than just a piece of cloth. This article delves into the origins of the bandana, its association with the paisley pattern, its political symbolism, and its continued influence in popular culture.

Origins of the Bandana

The word "bandana" is thought to derive from the Sanskrit word “badhnati”, meaning “to bind” or “to tie.” The term traveled through Portuguese as “bandannoe” before being anglicized to "bandana" in the mid-eighteenth century (Lynton, 2012). Early bandanas were introduced to Europe through colonial trade from South Asia and the Middle East, gaining popularity in Western cultures by the late 17th century. Bandanas were made from cambric, a plain-woven cotton fabric, although silk versions were also common (Campbell, 2005). These square-shaped cloths featured vibrant prints, making them distinct from their predecessor, the kerchief, which was typically made from linen and often devoid of decorative designs.

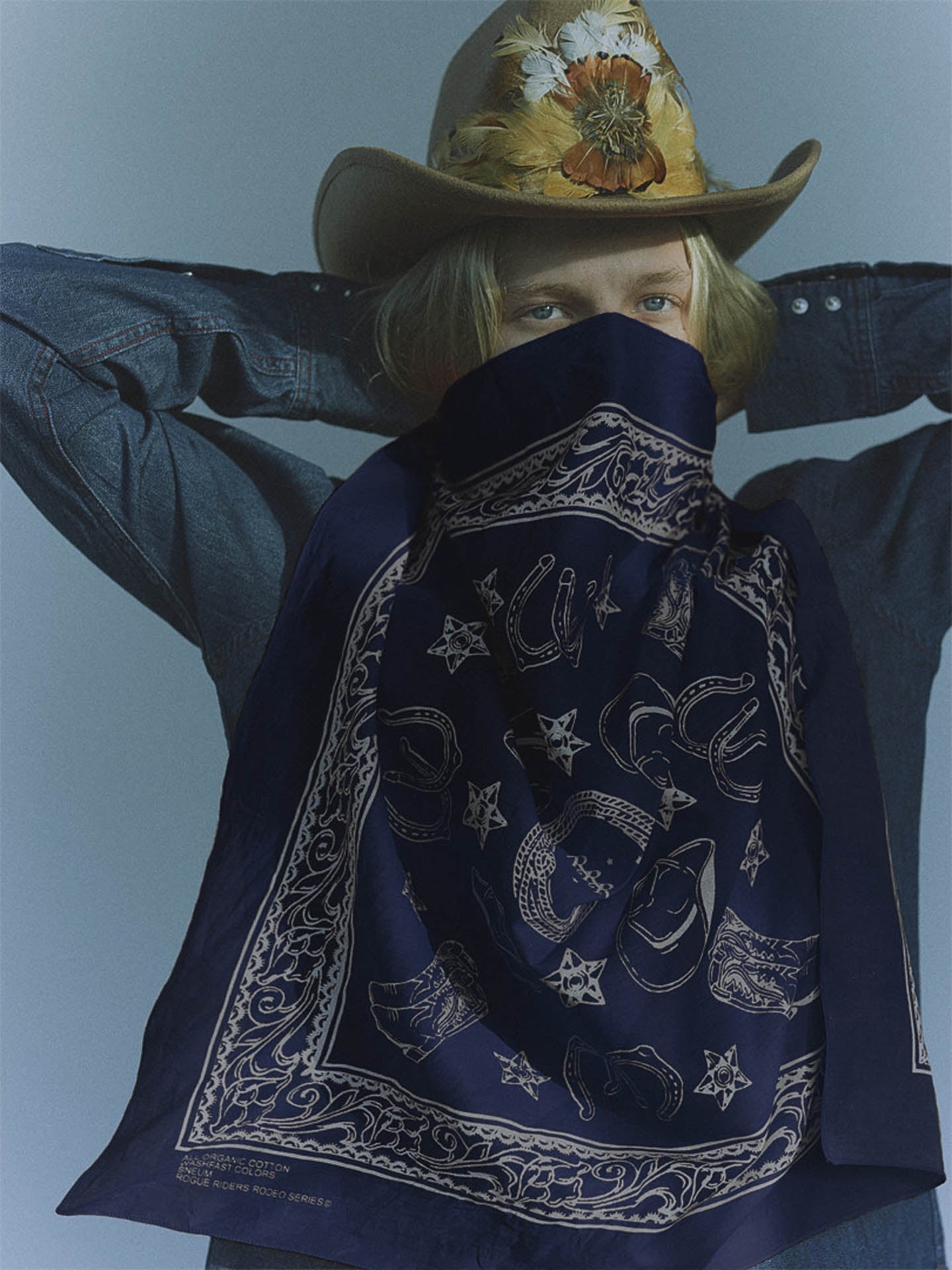

The practical use of bandanas became widespread among sailors, farmers, and workers who needed protection from the elements, such as sun or dust. In North America, the bandana found particular favor among ranchers and cowboys, who used it as a versatile tool, much like modern-day scarves (Lynton, 2012).

From Persia to Paisley: The Evolution of the Pattern

One of the most recognizable patterns found on bandanas today is the paisley motif. Contrary to popular belief, this pattern did not originate in Paisley, Scotland, but rather in the region of Kashmir, which was once part of the Persian Empire (Crill, 1999). In Persian, the pattern is known as “boteh”, meaning “bush,” “shrub,” or “leaf.” The boteh design, dating back over 2,000 years, symbolizes life, fertility, and eternity in Persian and Indian cultures (Welch, 2015).

During the 18th century, woven Kashmiri shawls adorned with boteh patterns became highly desirable in Europe, thanks to their luxurious texture and intricate designs. These shawls, imported through the Dutch East India Company, became symbols of status among European elites (Crill, 1999). Due to the high demand and scarcity of these expensive imports, manufacturers in Paisley, Scotland, began producing their own versions of shawls with similar designs, which is how the name "paisley" became associated with the pattern (Welch, 2015).

While originally reserved for high society, the paisley design eventually made its way onto more common items, such as bandanas, where it has remained a staple ever since. In Western culture, this lopsided teardrop design took on various regional nicknames, from "Persian pickles" in the U.S. to "Welsh pears" in Wales (Lynton, 2012).

Bandanas and Political Symbolism

The bandana has long been more than just a fashion accessory; it has also played a significant role in politics and social movements. One of the earliest examples of its political use can be traced back to the American Revolution, when Martha Washington produced bandanas to promote her husband’s military campaign (Cummings, 1989). These bandanas, adorned with patriotic motifs, demonstrated how a simple piece of cloth could serve as a powerful political symbol.

During the early 20th century, bandanas became particularly important in labor movements in the United States. Miners in the Appalachian region frequently wore red bandanas for both protection from coal dust and as a sign of solidarity during labor strikes. This practice was most notable during the Battle of Blair Mountain in 1921, where striking coal miners wore red bandanas to identify themselves, leading to the term "redneck" being coined (Savage, 2004). While "redneck" later took on broader connotations, it originally referred to these miners who used the red bandana as a symbol of unity in their struggle for labor rights (Coggins, 2015).

In the mid-20th century, the bandana became a symbol of rebellion and protest during the civil rights, feminist, and LGBTQ+ movements. Activists often wore bandanas to signal solidarity, and in some cases, to hide their identities during protests. Groups such as the Black Panthers and anti-war demonstrators adopted the bandana as a visual symbol of resistance (Lynton, 2012).

The Bandana in Popular Culture

By the late 20th century, the bandana had fully integrated itself into popular culture, becoming a symbol of both rebellion and style. In the 1960s and 70s, rock musicians like Jim Morrison and Bruce Springsteen wore bandanas on stage, contributing to the bandana’s association with blue-collar identity and the counterculture movement (Crill, 1999). Bruce Springsteen’s use of the bandana in his Born in the USA album imagery further solidified its place as a symbol of working-class America.

In the 1980s and 90s, the bandana took on new meanings within the emerging streetwear and hip-hop cultures. Tupac Shakur, one of the most prominent figures in hip-hop, frequently wore bandanas, especially tied around his head in a signature style that has since been emulated by countless fans. This use of the bandana was not only a fashion statement but also an expression of identity within the context of urban street culture (Welch, 2015).

In addition, the bandana has been used within the LGBTQ+ community, particularly through the "hanky code," where different colors of bandanas worn in specific pockets signaled sexual preferences and identities. This coded form of communication allowed individuals to express themselves in a discreet manner during times of greater social stigma and danger (Lynton, 2012).

Today, the bandana remains an enduring fashion accessory, worn by a wide variety of groups ranging from bikers and farmers to celebrities and fashion designers. Its versatility as both a functional tool and a powerful symbol ensures that it will continue to hold cultural significance for years to come.

Conclusion

The bandana’s journey from the ancient textile traditions of South Asia and Persia to its role in modern fashion and political symbolism highlights its enduring versatility. Whether used for practical purposes, as a symbol of rebellion, or as a statement of identity, the bandana continues to adapt and thrive within various cultural contexts.

References

- Campbell, S. (2005). Textiles in Transition: The Spread of Patterns in 18th-Century Europe. London: British Museum Press.

- Coggins, J. (2015). Redneck Nation: A History of the Working Class in America. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

- Crill, R. (1999). Indian Textiles: The Fabric of a History. London: V&A Publishing.

- Cummings, J. (1989). George Washington and the American Revolution: The Role of Propaganda. Journal of American History, 14(2), 45-60.

- Lynton, L. (2012). The Spirit of the Cloth: Textiles and Cultural Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Savage, L. (2004). The Battle of Blair Mountain: The Miners' Uprising and America's Forgotten Civil War. New York: Knopf.

- Welch, S. (2015). Paisley: The History and Cultural Impact of the Iconic Design. New York: Fashion Studies Quarterly.

sneum.com

Bandana with selvedge

Share